Disclaimer: In my day job, I work with some of the databases and services I’ve mentioned in this post. I wrote this in my own time, unpaid, using common knowledge held by any cataloguing librarian, entirely independently of any of these organisations.

As an author or a creator it’s important to make sure people can find your work and connect it with your name. It helps to build your reputation, and secure your income. But there are risks, too. I bet you’ve thought about this before yourself – all the ways you can uniquely identify yourself as different to another artist with the same name, are the ways your bank or hospital might verify your identity.

The same is true for libraries. A lot of authors, illustrators, musicians have the same names, and that can make it difficult for readers to find the things that they want to borrow. But making your names unique to help readers, can cause problems for your personal privacy.

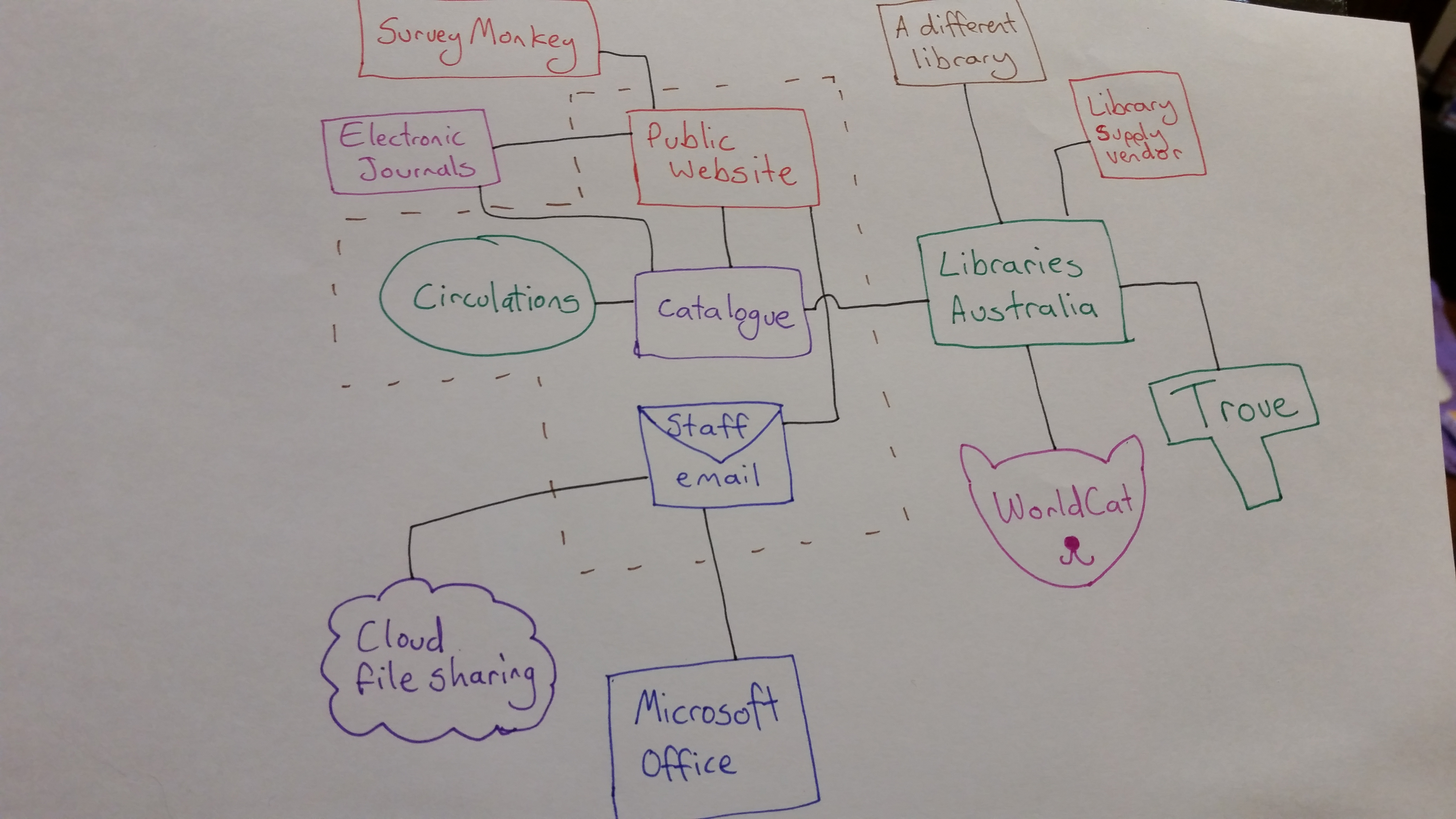

Back when libraries stored information in card catalogues, this information was protected by obscurity. There is a lot of effort involved in physically getting into a library and sifting through a drawer of cards. When we started sharing these records between libraries, they would be printed or typewritten and sent in the post. It was boring stuff nobody really cared about except for librarians. But since the 80s and 90s most libraries have moved to digital systems, and from there to cloud systems and shared online databases.

This has made library catalogue information about authors more exposed to the general public. Librarians have been discussing the best ways to reduce risk and improve privacy for a few years now. But I’m not sure anybody has reached out to authors or other creators. I’ve written this for creators to help you understand and navigate the weird and wonderful world of library metadata.

I’ve structured this with headings to make it easier for you to come back later and re-read the sections most useful to you.

Why do librarians collect personal information about authors?

Libraries are all about organising information to help library users access it better. Linking books, journals, art, music, and other things made by the same person can help people find what they want. These days, you’ll see it as a hyperlinked name in a catalogue record when you look at a catalogue record. Click it, and you get taken to a list of all the other things that person has been involved with.

But a lot of people have common names, so librarians have to find ways to make that difference clear to the public, and to our computer systems.

Other places face these problems, too. IMDB, Wikipedia, Academic repositories, and of course banks and health providers. Anything that keeps records about humans has this problem.

What data do librarians collect?

Libraries have a very long history of collecting and recording data. Our rules have changed over time, and this has changed what kinds of data we collect.

Most librarians try to collect the bare minimum amount of information, and often we will only record your given name and surname. The more people out there with your name or pseudonym, the more likely it is that a librarian will record more information about you to help differentiate between two people.

In Australia, this information tends to be recorded by the librarian (or library supplier) who is processing a copy of your book. If your stuff is published in the United States of America, and a copy is sent to the Library of Congress, American librarians will also record information according to their own rules (and the same goes for the UK, or other countries you are published in).

There are some Australian libraries that specifically collect Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander publications. The Australian Institute of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Studies (AIATSIS) makes headings that are different to other databases, because their headings prioritise how Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people want to refer to themselves, and this can be very different to the rules librarians must follow with other standards.

How is this data used?

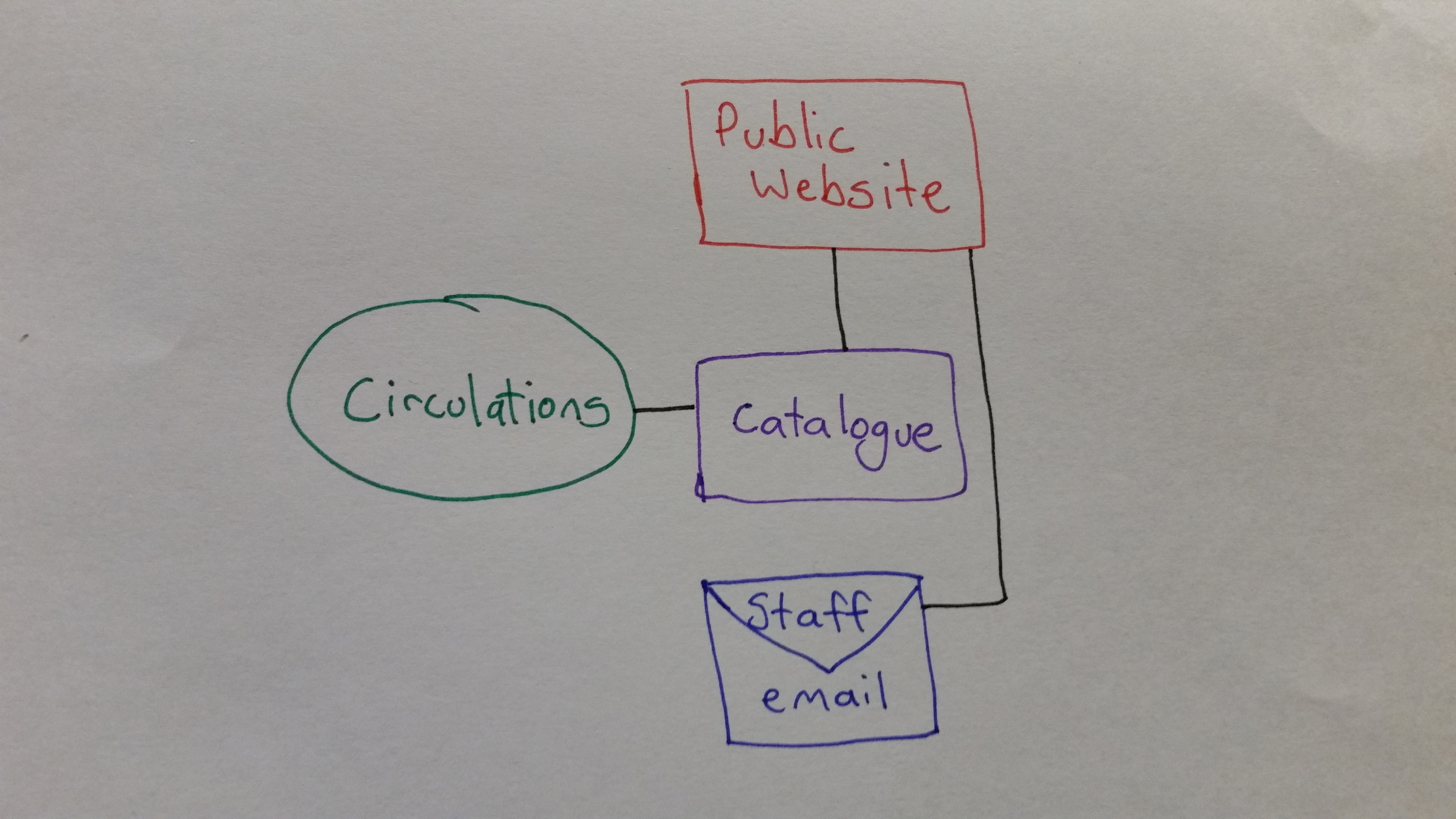

We record information about authors and creators in two places.

1 – The catalogue record.

This is what people browsing a library catalogue will see. It can be plain text entered by a librarian, which is most records.

This can be as simple as Lastname, Firstname.

But if you have a common name or you are a notable author, they will link to something else too. That link is to something we call an “authority record”.

The catalogue record itself can also contain a little detail, to make sure you do not accidentally match with an existing Authority Record. This can include your middle name, life dates, or expanded initials.

Lastname, Firstname, 1965-

Psuedonym, 1920-2010

Lastname, F. M. (Firstname Middlename)

Pseudonym (Full Legal Name), 1989-

Most Australian authors will only need to worry about this information in the catalogue record.

2 – An Authority Record. These records can be made for people, organisations, government bodies, places, and ideas. This record contains detailed information to help librarians choose between two similar people or things, so they know which one to use in the catalogue record.

What goes into the authority record depends on how many other people share your name, how much information the librarian can find, and even when the record was made.

Most librarians will first use your year of birth or death, or a middle name, whichever is easiest to find. Some will call your publisher, and others will search online. Information printed in the book – think about your forewords, afterwords, and author bio – and on your author website, are the most commonly used.

Some people have very common names, and they may have their month of birth or even day of birth recorded. This has not been done a lot in the last few decades, as society as a whole has become more aware of digital privacy, but authors who have been writing before the 90s may have had their record created long before this shift.

We have cataloguing rules, and these rules have changed over time. Depending on which year the record was created – which may not be when you started writing, but when somebody with the same name as you started writing – different standards applied. Some people had records made at a time that their profession or awards were recorded. Other people came into our shared databases right after some new rules for recording gender were written, before most of us realised it was tacky to out authors as transgender for no good reason. There are a lot of options available to cataloguers, which is meant to make us more flexible in what we record, but together the options can feel more invasive than simply a middle name.

Finally, people who write under pseudonyms or collective pseudonyms might have their names directly associated with their legal names or deadnames in authority records. Normally this only happens when an author or publisher makes a direct connection between the names in a publicly visible way, but sometimes pseudonyms can be connected without the author releasing this information to the general public domain.

Where do librarians get this stuff from?

It depends on the librarian. There are a few common places we get the information from, all public and published. Fortunately, it means you will have a lot of control in the future. Unfortunately, it means that if the information is already out there there’s not much you can do to un-publish it:

Author bios and blurbs in the book itself

Letters, pamphlets, and other things sent to the library with the book

Author websites, and author bios on publisher websites

Interviews, news articles, and social media posts

ONIX files (a kind of metadata file publishers can send to bookstores and online booksellers), and other marketing material publishers share with bookstores

Direct contact with the publisher

I think it’s great practice for everyone to blacklist certain types of information from social media – your exact age and birthday, your local shops and where you live, your full legal name. Your first dog, your primary school, etc. If you are comfortable sharing this information, that’s fine, but it might show up in places you don’t expect. When in doubt, do not share anything in the public eye that could be used to pass a security question with your bank.

Sometimes when I used to do cataloguing work, we librarians would call up publishers or email them asking for information to help make authority records for authors with common names. We always asked the publisher to make sure authors had given permission for publishers to share that information with us, but I’m honestly not sure what publishers tell authors. I think that publishers trust us, because we are librarians. And we trust publishers, and… yeah.

You should totally be able to ask your publishers and agents to refuse to share this information if you’re not comfortable with that. If your publisher doesn’t know, or doesn’t know how to protect your privacy, I think that is a conversation worth starting with them.

Which authors are affected?

Authors who have names in common with other authors are the most likely to have more information recorded. But it really does depend on the library and the librarian, as well as when you started writing. Some librarians used to make a lot of authority records, and they made fewer and fewer over time. These days, the places I have worked are more cautious as digital privacy issues emerge.

Sometimes, the book distributors who feed automatic or pre-publication data into library systems, can take information you enter into your account and pass it on, unintentionally revealing identities.

There are also smaller changes to our rules, that made it possible to record information on gender, that could traumatically out somebody. Sometimes there’s a few records that were created before librarians realised a new option was potentially harmful. It’s hard to predict who is affected, because it is bad luck. Most of the time librarians fix the records they know about.

I have noticed that authors who write under known pseudonyms, and authors who transition while continuing to publish, also tend to have authority records created to link their different names. Some librarians think it’s really important to link everything together as much as possible. I personally think it’s unnecessary to link deadnames and pseudonyms together unless the author or publisher makes it clear to me that this is what they want. I’m talking, unless an author calls up and asks me to do it, I will not link these records. But these practices vary depending on the country, culture, and values each library operates in.

All authors will have their name recorded in a catalogue record as it appears on the book, too. It looks like this:

Lastname, Firstname, 1988-

My first book : a novel / Nickname A. Lastneam

In other words, if there’s a typo in the book cover, there’s going to be a typo somewhere in the catalogue record to match it.

So all authors are affected, but some authors are more affected than others. Yeah, it’s confusing and weird. But I hope that helps you look at library data and see how it affects you.

How can I find out what is stored about me?

There’s a lot of libraries to check. I’ve got some tips to help you find the data in shared online public databases, but you will have to check individual libraries.

In Australia, Trove lets you search records contributed by the vast majority of Australian libraries. You can search for catalogue records and see which libraries have copies of your books and other things by clicking into each search result and looking for the “borrow” or “read” tabs. You may need to look in a few categories, but most authors will be in the books and libraries, or diaries and letters categories.

The database behind Trove also sends data to WorldCat. WorldCat will have Australian records, and records from other countries too! The lists of libraries will be much longer, especially if you are published in the United States.

For the authority records that link to the catalogue records, you can search most Australian records in Trove – there’s a “People” category . Though do be aware, that’s got records from a bunch of other databases, it’s not just library data. For the records made in the United States, check out the Library of Congress Authorities search .

If your books are published in Europe, Japan, China, or other areas you will need to look into how those countries organise their library data. Some areas share records based on language of the books, or geographic regions, or other things. Your publisher or the national library of the countries you are published in should be able to get you started.

Can I change it or take it down?

Yes and no. It depends.

When you get in touch with a library to ask for changes, it is useful to say that you do not want your middle name or year of birth recorded, and ask if they have other alternatives to help differentiate you. You don’t need to have a plan for what you want changed until you speak with the librarian. In fact, all you need to do is tell them what you don’t want recorded, and ask them what they can do to help you.

But what they can do to help you will depend on how their library is run, where their records come from, and how much capacity they have to take on this work. I’ve said a bit more on this further down.

Now let’s talk about how changes are made.

The shared databases Trove and WorldCat (and other ones around the world) get their records from individual libraries. Normally, records flow upwards to the shared databases when they are created in a library, but they only come down from a shared database when a librarian manually brings them down. So information can get added quickly, but removing it means a lot of individual points of contact.

If your books are in 2-3 libraries it’s a quick process to contact each library and ask them to change the data. It might take longer for the changes to be uploaded to the shared databases. If your books are in 10+ libraries, that work gets harder.

My recommendation is to start with the biggest or best funded library you can find for each of your books. A lot of smaller public and university libraries have had budget cuts in the last year, so they might be slower to reply to you. If you can get the record in Trove or WorldCat updated, it’s a lot easier for librarians at smaller libraries to copy the fixed version. But even with bigger libraries, it can take months for librarians to work through the list of requested changes. Ask any librarian how long it takes us to get the Library of Congress to update one of their subject records… yeah. On the plus side, if you’re polite and patient librarians will do their best to help you.

If the information you want to change appears in the book itself, the librarian cannot change the catalogue record. This is because we need to be able to match the books to the records, and a reader might write down that information to try and find it again. I’ve had a few heart-rending requests to remove ex-lovers from catalogue records, and I feel awful when I have to tell them that I can’t change it because it’s on the book cover and my record must represent the book that was published.

If the information is in an authority record, you can change more things but the process can be much slower. Normally authority records specify where their information came from. I wanted to take a screenshot, but honestly I felt uncomfortable copying and pasting that information in a blog. Please search and see for yourself, instead.

The source of information can include from the publisher, or from websites or newspapers. So although it changing a Library of Congress record is slow, while you wait you can use the record to follow up and ask the listed sources to take down any information you do not want shared, too. You’ll find it to the right of the number “670” – all the data fields have numeric codes.

If you’re published in the United States, find an American library that holds your books and ask them for advice about the Library of Congress authority records. They can hopefully help you navigate things.

But the library website has a privacy policy

These policies are normally for library users – people who sign up to use the library catalogue or online booking services. Catalogue records and authority records are covered by the library’s internal polices. These might be called “Collection Development Policy” or “Collection management guidelines”. Some libraries will have separate policies for authority records and books, and other libraries will purchase catalogue and authority records as a bundle from a library supplier and will treat the whole lot as part of their library collection.

The best way to find out what privacy rules a library is applying to your name in catalogue records, is to ask them in an email. You might get lucky and find some information on their website, but most libraries have a team working on the website who is focused very specifically on helping borrowers and visitors to the library. They usually don’t know the details of the catalogue records or the policies that govern how the records are managed.

Help, this is overwhelming!

Yeah. It’s frustrating and overwhelming for librarians, and it’s got to be much harder looking in from the outside. It is a lot of work.

Most Australian authors like you are going to search in Trove and WorldCat, and discover that everything is okay. It will be a fun exercise to see who has copies of your books.

But if you’ve been writing for a long time, or have a common name, or included more information than you realised in your author bios, it might feel very stressful. It’s a lot of work to chase this stuff up, especially when you have to learn about library data.

Take your time. Remember that this information is generally out there in the public, and what you are doing is a mindful way of controlling your public exposure.

Remember that librarians are discussing author privacy, and all the risks of our legacy data from the past. We don’t have an answer right now but people are working hard to improve things. In the meantime, you can have more control and feel more confident about what libraries store about you.

A librarian’s top tips for authors

- If you haven’t published yet, decide whether you would like to use a pseudonym or use initials instead of your full name. Use that name on all your books, your website, and social media. Or choose one thing to obfuscate – the year of your birth, or a middle name – so you can use your real name for publishing but you protect the personal details that you use for online banking.

- Never ever ever ever use information in a catalogue record or your author bio for a “secret question” or answer in your security settings. That includes your fictional characters names, pets, and favourite foods.

- Talk to your publisher, agent, and anyone else you work with when you publish your books. Advocate in your own industry for better personal data privacy, and this will improve the privacy of the data that is fed into library records.

- Seeing your personal information in a catalogue record can come as an unpleasant shock. Before you do anything, take care of yourself. This is not your fault, or the library’s fault. It’s a systemic problem affecting multiple industries as our society moves into a more digitally connected future. You might feel unsafe, scared, angry, or sick. It’s going to be okay. Librarians care about your privacy and we’re doing our best to try and make it better.

- If you do find library records that you want to change, break it down into smaller steps and tasks that can fit around your writing schedule and life. Librarians are going to take ages to get back to you, so there’s no rush to do this all at once.

- If it is too overwhelming, or uncomfortable, get a trusted friend to do the legwork and help you work through the process of finding your records and asking libraries to change them for you. It’s really repetitive and there’s no reason you have to do this all by yourself. A lot of people who are doxxed or exposed rely on their friends to do very similar things on social media. That support makes a huge difference.

- You won’t be the first or last author to ask us to change your details. Some libraries might not have the capacity to change everything right away, but it is reasonable to ask for private personal information to be removed from your records, and all libraries get questions about their catalogue records. It is always okay to ask us questions.

- When you ask people to change things, make sure you ask them for help getting the changes updated in Trove and WorldCat too. That way the next librarian who copies that record, gets the updated version.

Can I use this or share this with other authors?

YES please do!

I make most things I write about libraries Creative Commons.

I care a lot about online privacy a lot. I would love for this to reach as many authors in Australia as possible.

Please credit me or cite me as a source. You are welcome to copy this in full, or re-use parts of it. Please adapt it to suit yourself or your community.

I know that the Australian writing community often depends on workshops and consulting to break even. It is okay to use this commercially in any way that is useful to you, but please make sure you let people know it is also available freely online here.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.